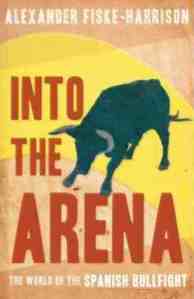

“Into The Arena” stands as a seminal work on bullfighting, unparalleled in its depth and perspective among English language texts. Its blend of personal narrative and cultural analysis elevates it beyond a mere account of the corrida, positioning it as a key reference for understanding the complex interplay of tradition, art, and ethics in the bullfighting arena.

Chat GPT 4.0

“Complex and ambitious. Compelling and lyrical.”

*****

Mail on Sunday

“An engrossing introduction to Spain’s ‘great feast of art and danger’…brilliantly capturing a fascinating, intoxicating culture.”

Sunday Times

“A compelling read, unusual for its genre, exalting the bullfight as pure theatre.”

Sunday Telegraph

“Thrilling. An engrossing introduction to bullfighting.”

Financial Times

“A powerful and compelling view into an unknown world.”

The New York Times

“Incredibly engaging… pulses with the writer’s love of the world and the people he has found himself among.

The Australian

“The Englishman who became the great expert on bullfighting.”

¡Hola!

Into The Arena is available in paperback or as an e-Book

From the front cover:

A hero from another age, a fearless Englishman touched by madness. This endeavour owes as much to Captain Oates as to Ernest Hemingway, as much to Flashman as to Don Quixote.

Giles Coren, columnist for The Times

Arguably the most engaging study of bullfighting by an English speaker since Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon. His willingness to get his hands dirty, and his eye for detail, make this a compelling read for anyone interested in Spain’s ‘national fiesta’. Controversial, thought-provoking and highly recommended.

Jason Webster, author of Duende: A Journey In Search Of Flamenco

Bold, provocative and morally searching, Fiske-Harrison writes about the bizarre and arrogant world of bullfighting with passion, deep knowledge, and readiness to risk his own neck in the arena. His descriptions lucidly capture the near indescribable thrills of the corrida.

Michael Jacobs, author of Factory Of Light: Life In An Andalucian Village

From the back cover:

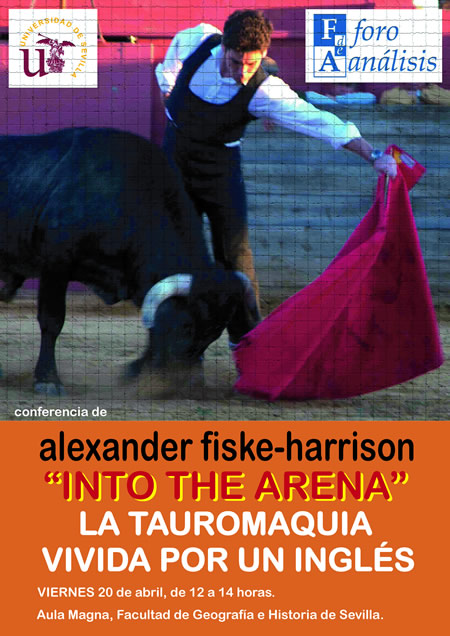

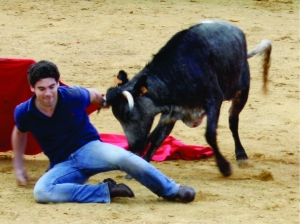

Alexander Fiske-Harrison spent a season studying and travelling with the matadors and breeders of famous “fighting bulls” of Spain (and France and Portugal. ) He ran with the bulls in Pamplona and found himself invited to join his new friends in the ring with 500lb training cows. This developed into a personal quest to understand the bullfight at its deepest levels, and he entered into months of damaging and dangerous training with one of the greatest matadors of all, Eduardo Dávila Miura, to prepare himself to experience the bullfight in its true essence: that of man against bull in a life or death struggle from which only one can emerge alive.

From inside the cover:

“The bullfighter-philosopher.”

John-Paul Flintoff in The Times.“Whether or not the artistic quality of the bullfight outweighs the moral question of the animals’ suffering is something that each person must decide for themselves – as they must decide whether the taste of a steak justifies the death of a cow. But if we ignore the possibility that one does outweigh the other, we fall foul of the charge of self-deceit and incoherence in our dealings with animals.”

Alexander Fiske-Harrison (writing in Prospect magazine in 2008)“It is one of the best pieces ever written on the subject. An almost literally terrific piece of work.”

Frederic Raphael (on Fiske-Harrison’s 2008 essay).

Alexander Fiske-Harrison (personal website here) was born in 1976 and English prize-winning author and journalist, broadcaster and conservationist. He studied biology and then philosophy at the universities of Oxford and London (and trained in acting at the Stella Adler Conservatory in New York under Marlon Brando) and works works as a postgraduate at the School of Neuroscience at King’s College London. He has written for, and been interviewed in The Times, Financial Times, Daily Telegraph, The Independent, The TLS , Spectator, Prospect and Condé Nast Traveller, GQ and Tatler magazines and ABC, El Norte de Castilla, Diario de Navarra and ¡Hola! magazine in Spanish. He has appeared on the BBC, CNN, Al-Jazeera, RTVE España and the Discovery Channel with Bear Grylls. He wrote, and acted in, The Pendulum which debuted in London’s West End in 2008.